The second-hand clothing market was built on a simple ideal: providing affordable clothing to those in need by giving unwanted goods a new home. As op shops evolved into a method for charities to fund aid efforts, stores ‘traded up’ to better cater to the general population. However, greater community awareness came with an influx of poor-quality donations, forcing stores to send items to landfill or the Global South. The problem of waste was compounded by the digitalisation of thrifting, with apps like Depop mimicking social media formats to promote perpetual consumption. While lengthening the lifespan of clothing may seem like a sustainable alternative to fast fashion, today’s second-hand market risks undermining the circular economy by failing to slow waste production.

Breaking the second-hand stigma

In 1890, 25 years after founding the Salvation Army, William Booth published In Darkest England and the Way Out. Concerned with the extreme poverty plaguing English society during the Industrial Revolution, Booth outlined a welfare state where society – not just charities – took responsibility for aiding the needy. In one proposal, he suggested redistributing ‘excess’ in well-off homes to support ‘submerged’ communities. The resulting ‘salvage stores’ offered a random assortment of clothing, sewing machines, and chinaware, priced low to avoid haggling.

Bar the basic principle of selling goods at a shopfront, salvage stores bore no resemblance to retail. They were in and of themselves charitable efforts; the sole audience was disadvantaged individuals trying to access basic goods, and revenue barely covered expenses.

The modern op shop model arose in 1947, when Oxfam converted surplus clothing donations into cash to fund its charitable work. The idea was popular among charities, which, by using volunteers and accepting donated products, could minimise overheads for an almost guaranteed increase in funding. At their inception, op shops embodied Stage 1 of Malcolm McNair’s Wheel of Retailing model: businesses attract their first customers with low prices, made possible by low operating costs.

However, these new stores were often located in poor areas, creating stigma around second-hand fashion. Visible signs of wear became a subtle marker of not being able to afford new, and the public, though proud of donating, wouldn’t admit to buying. This stigma presented a challenge for charities, which needed a wider audience to generate store revenue and fund aid efforts.

To improve brand reputation, op shops entered the second phase of ‘trading up’, adopting strategies from for-profit stores to enhance retail atmospherics. Research shows that superior organisation, style, and modernity cause 63% of customers to spend more time in-store and 45% to spend more money. In a thrift store context, this meant volunteers took on more specialised roles in sorting, pricing, and merchandising goods. Dressed windows and coordinated colour schemes were introduced, alongside curated ‘retro’ and ‘designer’ sections.

These expansion efforts proved wildly successful. In 2021, 72% of Australians reported purchasing at least one second-hand clothing item. Vinnies’ New South Wales branch saw a 50% increase in funds raised between 2023 and 2024, along with a 56% increase in customers. As thrifting became normalised, the stigma attached to used items declined, benefiting the original customer base.

Stage 3 of McNair’s model entails a business failing to deliver strong returns due to high operating costs. Specifically, at the point of producing premium products through their hierarchies of retail management, retailers are inevitably replaced by a new crop of cheap stores. Interestingly, the nature of op shops has enabled them to bypass this final ‘maturity’ stage. Even with more labour directed toward improving retail atmospherics, there is a limit to improving customer experience within the scope of donations. Charity shops have consequently kept costs low and maintained their initial appeal of affordability.

Op shops or dumping grounds?

The downside of supplying donated goods is that merchandise quality is ever-changing, and not necessarily for the better. In an age where personal sustainability has wormed itself into public consciousness, it’s easy to recognise that durable goods can last longer than you’ll keep them. And for most, dropping a bag off at the nearest donation bin isn’t much harder than throwing it in the rubbish.

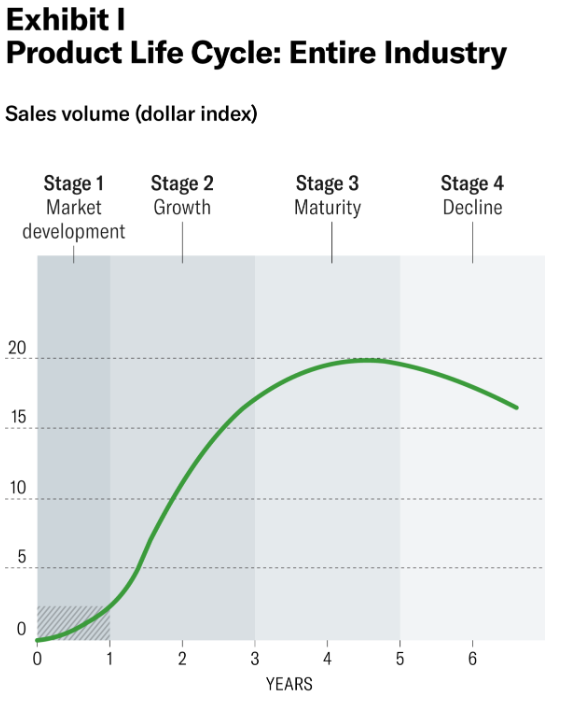

But how durable is clothing? According to most estimates, not very. Mass-produced, cheaply made items are designed to last about 10 wears, as long as it takes for the next design to replace them. This falls severely short of the 3 years required to be ‘durable’, such that the average person accumulates more clothing that is ‘out of style’, or at the decline stage of Theodore Levitt’s product life cycle model.

Now that products hold little personal value, what motivates individuals to donate to charity? Mitchell et al. (2009) identified two streams of reasoning for choosing donation over disposal: self-interest and altruism. Self-interested reasons included cleaning up, purchasing new goods, and recognition of their goodwill. Altruism stemmed from a moral sense of obligation, reflecting Booth’s ideal of wealthy people helping disadvantaged members of their community. The most cited reasons for donating, seasonal cleaning (84%) and the need to free up space (78%), both fall under self-interest. The desire to help others and support the organisation placed third, cited by 60% of donors.

From a utilitarian framework, the distinction between self-interested and altruistic motivations has little consequence, as the outcome of goods being diverted from landfill remains the same. However, while donations have surged 38% in the past year, only 10-20% are suitable for sale, indicating self-interestedness could yield poorer quality donations. The remaining 80-90% are sent to landfill or exported to nations in the Global South.

In developing countries like India, Senegal, and Nigeria, excess donations follow three stages to squeeze the remnants of their remaining life. First, they are sold at low prices, which, as costs needn’t be recovered, undercuts local manufacturers trying to make a living. The remaining items are picked through to salvage remaining pieces, a task often left to women and marginalised communities. Finally, waste is dumped or burned on the streets, polluting waterways and diminishing air quality.

Streamlining second-hand shopping for instant gratification

Festinger’s effort justification model suggests that individuals place a higher value on rewards that come after significant effort. Conversely, Matthew Botvinick’s effort discounting framework proposes that when people believe their hard work won’t lead to a meaningful reward, effort has negative value. Of the two, Botvinick’s theory better applies to traditional retail; with all items displayed for you, there’s no reason to believe you’ll find more after a deeper search. Consequently, physical stores create a seamless shopping experience with accessible layouts.

Online shopping makes it even simpler, with filters and search bars designed to maximise the conversion of site traffic into sales. As some shoppers lament the treasure hunt style of thrift stores, the emergence of online second-hand marketplaces like Depop, Vinted, and ThredUp is no surprise. Sixty-five percent of global consumers use online shopfronts to purchase used goods. Depop stands out as the 10th most visited shopping site among Gen Z customers in the US.

The platform mimics Instagram’s algorithm by recommending users clothing based on what they’d previously saved or liked. Item listings often feature a paragraph of generic trend names to elicit clicks and boost reach. Customers can follow specific sellers and receive a curated feed of clothing recommendations, taking away the hunt and bringing items directly to them.

By streamlining the process of moving listings to cart, Depop’s algorithm encourages impulse buying to maximise sales. If Depop were a charity, it could be argued that this is a positive; more funds can be funnelled into community aid efforts. But Depop is a for-profit business, built to incentivise its sellers to sell more and drive demand. Its e-commerce model, which leaves the bulk of earnings to individual sellers, inherently encourages them to source products at the lowest possible cost and sell them at a significant markup. In some cases, individuals purchase low-quality, ultra-fast fashion goods for cheap and reframe them as ‘one-of-a-kind, pre-loved treasures’. Panju (2024) asserts this language co-opts the ‘market-oriented shrewdness of fast-fashion giants,’ greenwashing unsustainable products to cater to growing eco-consciousness.

A true circular economy both recycles goods and prevents the future production of waste. Online second-hand marketplaces may succeed in the former, but they disastrously fail in the latter. On the seller side, choosing to list a used item comes with the same motivations as donating: clearing out and not wanting to throw a product away. With the added incentive of recovering some of the sunk cost spent on purchasing the item, more shoppers are encouraged to extend the lifespan of their items by listing them on Depop.

However, from the buyer’s side, individuals continue to treat clothing as disposable. The market is flooded with upsold low-quality items, with no reliable gauge of how items will look or fit beyond product photos. The same principles of perpetual consumption in fast fashion apply; as buying gets easier, people value items less and accumulate more than they need.

Conclusion

Early salvage stores operated on a philosophy of redistribution and aid. Echoing the tried-and-true methods of fast fashion, today’s second-hand market has ‘traded up’ and adopted social media to drive sales. The resultant increase in thrifting popularity fails to address the fundamental issue of overconsumption. True sustainability requires a radical shift – not just in where you buy, but in how much.

Fitton, T., & Payson, A. (2024). Second-hand clothes can create a mountain of problems. This is why. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-03-16/second-hand-clothes-thrift-not-answer-to-waste/103585470

Grimmer, L., & Grimmer, M. (2022). Do you shop for second-hand clothes? You’re likely to be more stylish. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/do-you-shop-for-second-hand-clothes-youre-likely-to-be-more-stylish-180028

Harmon‐Jones, E., Matis, S., Angus, D. J., & Harmon‐Jones, C. (2024). Does effort increase or decrease reward valuation? Considerations from cognitive dissonance theory. Psychophysiology, 61(6). https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.14536

Horne, S. (2000). The charity shop: purpose and change. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 5(2), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.104

Irving-Munro, A., & James, A. (2025). The Consumption Economy - Finding Value in Our Clothing. Proceedings of the 6th Product Lifetimes and the Environment Conference (PLATE2025), 6. https://doi.org/10.54337/plate2025-10420

Katsaras, J. (2024). More Australians are turning to op shops, but it’s not just the cost of living driving the trend. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-05-08/australians-turning-to-op-shops-in-cost-of-living-crisis/103809766

Levitt, T. (1965). Exploit the product life cycle. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1965/11/exploit-the-product-life-cycle

Macklin, J. (2019). So you’ve KonMari’ed your life: here’s how to throw your stuff out. https://theconversation.com/so-youve-konmaried-your-life-heres-how-to-throw-your-stuff-out-109945

Mitchell, M., Montgomery, R., & Rauch, D. (2009). Toward an understanding of thrift store donors. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 14(3), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.360

Mohr, I., Fuxman, L., & Mahmoud, A. B. (2022). Fashion Resale Behaviours and Technology Disruption. Advances in Marketing, Customer Relationship Management, and E-Services, 351–373. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-4168-8.ch015

Morgan, L. R., & Birtwistle, G. (2009). An Investigation of Young Fashion consumers’ Disposal Habits. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33(2), 190–198.

Panju, M. (2024). What Goes Around Comes Around?: The Sustainability Paradox of Second-Hand Clothing Marketplaces in a Cross-Cultural Context. East African Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 7(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.37284/eajis.7.1.1799

Rayburn, S. W., & Voss, K. E. (2013). A model of consumer’s retail atmosphere perceptions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 20(4), 400–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.01.012

Smoleniec, B. (2023). Are charity shops too trendy to help the needy? ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-02-14/are-op-shops-becoming-too-mainstream-and-unaffordable/101957692

US EPA. (2017). Durable Goods: Product-Specific Data. US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/durable-goods-product-specific-data