Are ‘buy now pay later’ services (e.g. Afterpay, Klarna) financially innovative or a cause for concern? The rise of “Buy Now, Pay Later” (BNPL) services like Afterpay, Klarna and Zip Pay has been nothing short of meteoric. Recent estimates suggest that BNPL transactions totalled $342 billion globally compared to just $2 billion a decade ago[1]. Their uptake has coincided with the declining popularity of the credit card – ASIC data showing credit card accounts peaked at 15 million and are now down to 11.8 million as of 2022[2]. But the prevalence of BNPL has been met with controversy. For some, they epitomise the consumerism epidemic, seeking instant gratification by spending money they don’t have (cue the ridicule for financing a GYG order with Afterpay). For others, the fact that BNPL services operate in a relative regulatory wild west, in contrast to the highly regulated banking industry, causes concern for increased credit risk. But these are not new problems to consumer credit, and with some tweaks, BNPL could be the best form of consumer credit we have yet.

Déjà vu: The parallel with credit cards

In 1974, Bankcard was the financial innovation taking Australia by storm. As the first credit card offering domestically, it allowed everyday Australians to access credit at a moment’s notice and buy what they want right away even if they didn’t have the cash to pay for it in the moment. Consumers no longer needed to wait days or weeks, and provide extensive documentation for a personal loan, or alternatively, finish paying off their lay-by instalment plans before getting the item in their hands. Merchants could benefit from reaching more customers and getting more sales by accepting the card. It was popular. By 1976, there were already over a million Bankcard holders[3]. Of course, it was not without its controversy. Some businesses initially boycotted the card for its high transaction fees, others gawked at the 20%+ annual interest rates, and the government was concerned that popularising credit may lead to worse household financial health, and overspending[4]. To credit detractors, it seemed the introduction of credit cards was a sign of moral decay, being dubbed the ‘instalment evil’ by a particular newspaper[5]. But 50 years on, the ‘evil’ credit card has all but become commonplace in our payments mix. The latest RBA payments survey shows that it is the second most popular form of payment behind the debit card[6].

Today, BNPL sells a similar story of increasing access to credit. With just a few taps in an intuitive app, anyone could unlock a small line of credit and pay in interest-free instalments over a few weeks. And unlike lay-by, they could get the benefits of an interest-free payment plan while still getting the instant gratification of buying something straightaway! By eschewing the conventional credit checks and rigorous income requirements of the highly regulated credit card industry, BNPL offers a more flexible and frictionless experience. It could explain how, in just four years, it has grown to one-sixth the size of the credit card market, with over 4 million users to date[7].

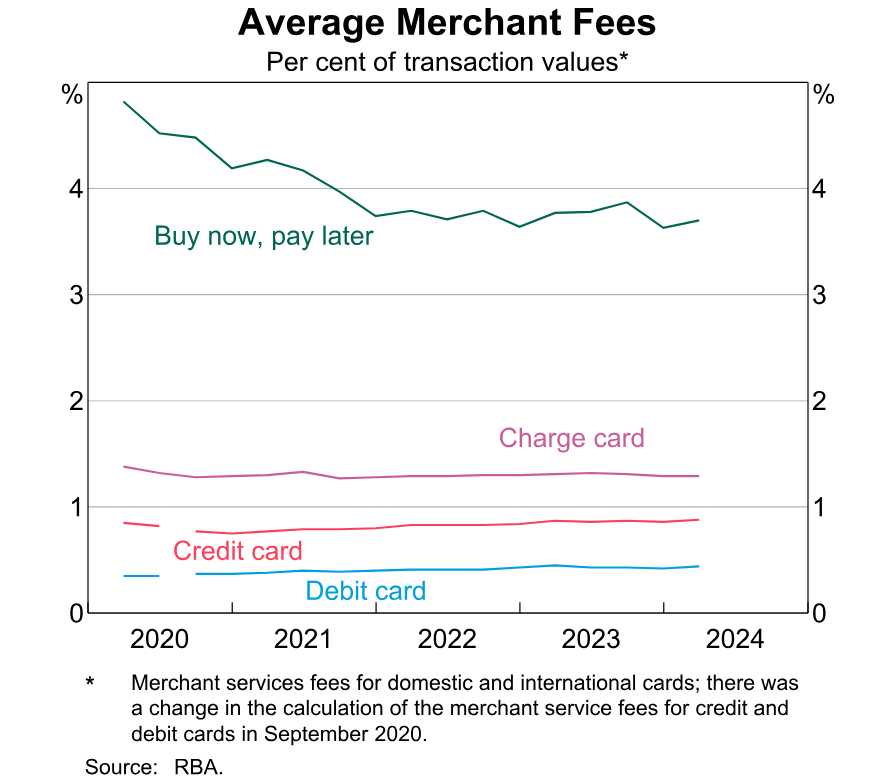

There are parallels to the problems faced by credit cards, too. While BNPL services do away with charging interest, late repayments could incur fees that are the equivalent, sometimes more, than the interest rates of a credit card[8]. Then, there is the problem of interchange fees. While credit card merchant fees are now regulated by the Reserve Bank, BNPL payments are not. This has meant much higher transaction costs for merchants, more than triple the cost of traditional credit cards[9].

There are also dangers of overspending, as research has shown a ‘price depreciation’ effect occurs where the perceived cost of buying something is lower simply because it is separated in time from the act of payment[10]. There is already evidence that consumers tend to spend more and more often than before with BNPL services[11]. But BNPL have a few differences that make it unique, with the potential to be better than credit cards.

Redefining what credit means

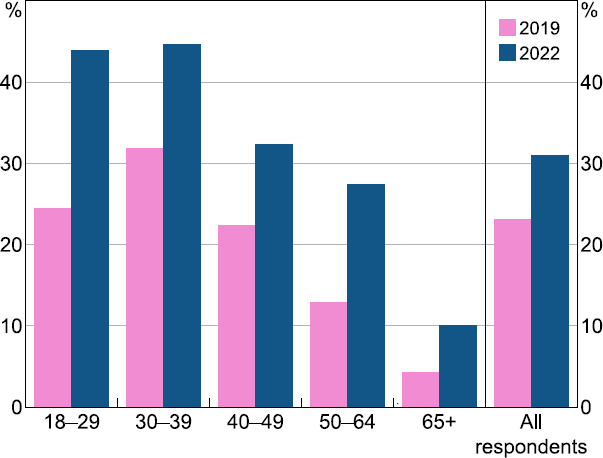

The key difference between credit cards and BNPL is access. BNPL platforms have tapped into a demographic that traditional credit often underserves: Millennials and Generation Z. In Australia, over half (53%) of the nearly 4 million BNPL users are under 30, while only about 10% of credit cardholders fall into this age group[12]. The digital-first experience of BNPL, where everything can be done on an app, is certainly attractive to the new generation of digital natives. But more importantly, BNPL provides those with non-traditional income sources or financial situations with an opportunity to access credit. Everyone from gig workers to a student working casual jobs here and there might not pass the income checks for credit cards, but are otherwise credit-worthy, could now access credit through a service like Afterpay[13]. And if the rise of BNPL over the past few years is any indication, it seems they are filling this gap well. Curiously, they are not being forced into BNPL either. Even if eligible for credit cards, many still choose to only have debit and BNPL due to the growing negative perception of credit cards among younger generations. Both globally and domestically, young people are increasingly viewing credit cards as complicated, stressful, or sometimes even predatory[14].

However, unlocking this new segment is not without its risks. These young people are also the most vulnerable to falling into financial traps. The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey showed Australians aged 15–24 had the lowest financial literacy rate out of all age groups[15]. Evidently, BNPL providers face a heightened responsibility to manage credit risk and prevent unwise financial decisions due to this literacy gap. By making the barrier to entry lower than traditional credit cards, BNPL players must do much more to support a more vulnerable population to take the right steps on their credit journey. Encouragingly, though, BNPL may just be the best way to dip their toes into the world of credit.

Unlike credit cards, BNPL services are relatively easier to understand. There are no complex interest calculations, minimum payments versus full repayments, cash advance fees, etc. The idea of making a purchase now and paying it back over 4 parts is perhaps as intuitive as they come.

BNPL services also avoid much of the credit card debt trap, which has given the product its negative connotations. BNPL services don’t charge interest at all on late repayments, only a late fee. In the case of Afterpay, this is $10 for a missed repayment, and another $7 if it is still not paid after a week[16]. Yes, it works out to be a worse deal for someone who just missed their $10 Afterpay repayment by a day. But in the long term and over many purchases, it prevents debt from spiralling out of control. BNPL requires the full repayment of your balance, unlike credit card companies, which let you scrape by with minimum repayments and let the interest pile on. And while credit cards let you keep spending if you’ve paid the minimum amount while being under the limit, most BNPL platforms immediately stop approving new purchases after a missed repayment. This avoids the dangerous revolving balances that let credit card users carry debt and continue to accrue exorbitant interest! Since each time consumers use BNPL is a self-contained debt with its own repayment plan, rather than a license to spend, consumers are better protected to spend within their means and ultimately, have a more responsible relationship with credit.

Indeed, BNPL services have more incentive to keep their users responsible compared to credit cards. BNPL providers’ revenue is largely generated from merchant fees. For example, Afterpay makes 80% of its revenue from merchant fees and only 20% on late fees[17]. Compare that with credit cards, which derive most revenue from interest payments and annual fees[18]. There’s no need for BNPL services to ‘trick’ consumers into forgetting to pay; they only need to make it so popular that it becomes second nature to use it.

In general, BNPL providers do a better job of fostering responsible use of credit. Whether it’s the simple fee structure, the requirement to repay your balance in full or the slick app that tracks your purchases clearly, it is perhaps no surprise that despite the less financially savvy and credit-worthy population using BNPL, debt default rates have stayed at similar rates to credit cards[19].

Of course, BNPL isn’t risk-free. But it does more than just extend credit for people to indulge in their materialistic desires. Whether intentional or not, it is likely to define for a whole new generation what credit means and how to use it properly. For that big of a job, we need to make BNPL the best it can be.

How Buy Now, Pay Later can be the better credit

Buy Now, Pay Later has a gleaming double-edged sword. It’s a novel offering, separate from the existing system of loans and credit cards, but that also means it’s a form of financing that’s not on financial institutions’ radar. While BNPL services were added to the National Credit Act earlier this year, mandating them to run credit checks on new customers, it is purely a one-way street[20]. That is, no financial institution can see someone’s BNPL history, whether they have defaulted, or have been on good behaviour. This is, of course, dangerous if someone overspends in BNPL platforms and subsequently is offered further credit from banks despite clear financial risks due to this blind spot. But it is also detrimental to consumers trying to build a history of good credit, for the inevitable occasion when they need to rely on traditional financial institutions for things like a mortgage. The onus is on both regulators and BNPL operators to increase interoperability and data sharing to promote safer and more integrated credit risk management.

On the flip side, we need to address the ‘true cost’ of using BNPL. Merchant fees are the bulk of BNPL providers’ revenue, meaning businesses are the ones who pay for the convenience, and they ultimately pass this cost down to consumers. For merchants, BNPL payments are often the most expensive form of payment they accept[21]. While credit card surcharges are regulated by the Reserve Bank, BNPL payments are not. Furthermore, most BNPL operators have contractual clauses that prevent the discrimination of users compared to regular card users. That is, they cannot surcharge customers for using BNPL over whatever fees might be incurred with regular credit or debit transactions. Merchants bear the brunt of consumers’ payment choices. As BNPL payments grow in popularity, the Reserve Bank should mirror the regulatory journey of credit card interchange fees, eventually applying a cap on merchant fees to maintain an efficient and cost-effective payment system.

Yes, new financial products should alarm us, and we are right to be wary about giving people the ability to spend what they do not yet have. But Buy Now Pay Later products need not be scary. They are already becoming the default form of credit for a whole new generation and doing a better job of teaching them about how to use credit than anyone before. By making BNPL products more open and integrated with the rest of the financial system, they can be a responsible, innovative and inclusive tool that further democratises credit, and empowers consumers to make decisions about their money.

[1] The Economist. (2025, August 4). Buy now, pay later is taking over the world. Good. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2025/08/04/buy-now-pay-later-is-taking-over-the-world-good

[2] Australian Securities and Investments Commission. (2022). ASIC report finds credit card debt still a pain for many Australians. Retrieved from https://www.asic.gov.au/about-asic/news-centre/news-items/asic-report-finds-credit-card-debt-still-a-pain-for-many-australians/

[3] Finder. (2025). A brief history of credit cards in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.finder.com.au/credit-cards/credit-card-history

[4] Sydney Morning Herald. (2019, October 9). From the archives, 1974: Major stores and unions reject Bankcard scheme. Retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/national/victoria/from-the-archives-1974-major-stores-and-unions-reject-bankcard-scheme-20191009-p52z49.html

[5] The Economist. (2025, August 7). Buy now, pay later gets a bad rap. But it could be genuinely useful. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/leaders/2025/08/07/buy-now-pay-later-gets-a-bad-rap-but-it-could-be-useful

[6] Reserve Bank of Australia. (2023). Consumer Payment Behaviour in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2023/2023-08/full.html

[7] Illion. (2020). Credit Card Nation. Retrieved from https://www.illion.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Credit_Card_Nation.pdf

[8] Financial Counselling Australia. (2022). Comparative analysis of credit card interest rates vs BNPL fees. Retrieved from https://www.financialcounsellingaustralia.org.au/docs/comparative-analysis-of-credit-card-interest-rates-vs-bnpl-fees/

[9] Reserve Bank of Australia. (2023, June). Consumer payment behaviour in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2023/jun/consumer-payment-behaviour-in-australia.html

[10] Gourville, J. T. & Soman, D. (1998). Payment Depreciation: The Behavioral Effects of Temporally Separating Payments from Consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(2), 160–174. https://doi.org/10.1086/209533

[11] Maesen, S., & Ang, D. (2024). Buy Now, Pay Later: Impact of Instalment Payments on Customer Purchases. Journal of Marketing, 89(3), 13-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222429241282414 (Original work published 2025)

[12] Illion. (2020). Credit Card Nation. Retrieved from https://www.illion.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Credit_Card_Nation.pdf

[13] Afterpay. (2024, June). Mandala Economic Impact Report. Retrieved from https://afterpay-newsroom.yourcreative.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/AP0437-Mandala-Economic-Impact-Report_Final-3.6.2024.pdf; Afterpay. (2025, June). Afterpay Experian Report. Retrieved from https://afterpay-newsroom.yourcreative.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/AfterpayExperian-Report.pdf

[14] Afterpay. (2025, April). Why Credit Cards Give Gen Z The Ick. Retrieved from https://afterpay-newsroom.yourcreative.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/AU-Why-Credit-Cards-Give-Gen-Z-The-Ick-_-White-Paper-External_MT.pdf

[15] Preston, A. (2020). Financial Literacy in Australia: Insights from HILDA Data. Retrieved from https://api.research-repository.uwa.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/73668586/Financial_Literacy_in_Australia.pdf

[16] Afterpay. (n.d.). Terms of Service. Retrieved from https://www.afterpay.com/en-AU/terms-of-service

[17] Reserve Bank of Australia. (2020). Afterpay’s Submission to Review of Retail Payments Regulation. Retrieved from https://www.rba.gov.au/payments-and-infrastructure/submissions/review-of-retail-payments-regulation/afterpay.pdf

[18] Illion. (2019). Credit Card Nation 2. Retrieved from https://www.illion.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Credit_Card_Nation_2.pdf

[19] The Economist. (2025, August 7). Buy now, pay later gets a bad rap. But it could be useful. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/leaders/2025/08/07/buy-now-pay-later-gets-a-bad-rap-but-it-could-be-useful

[20] Australian Government Treasury. (2022). Government introduces consumer protections for Buy Now Pay Later. Retrieved from https://ministers.treasury.gov.au/ministers/stephen-jones-2022/media-releases/government-introduces-consumer-protections-buy-now-pay

[21] Reserve Bank of Australia. (2023). Consumer Payment Behaviour in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2023/2023-08.html